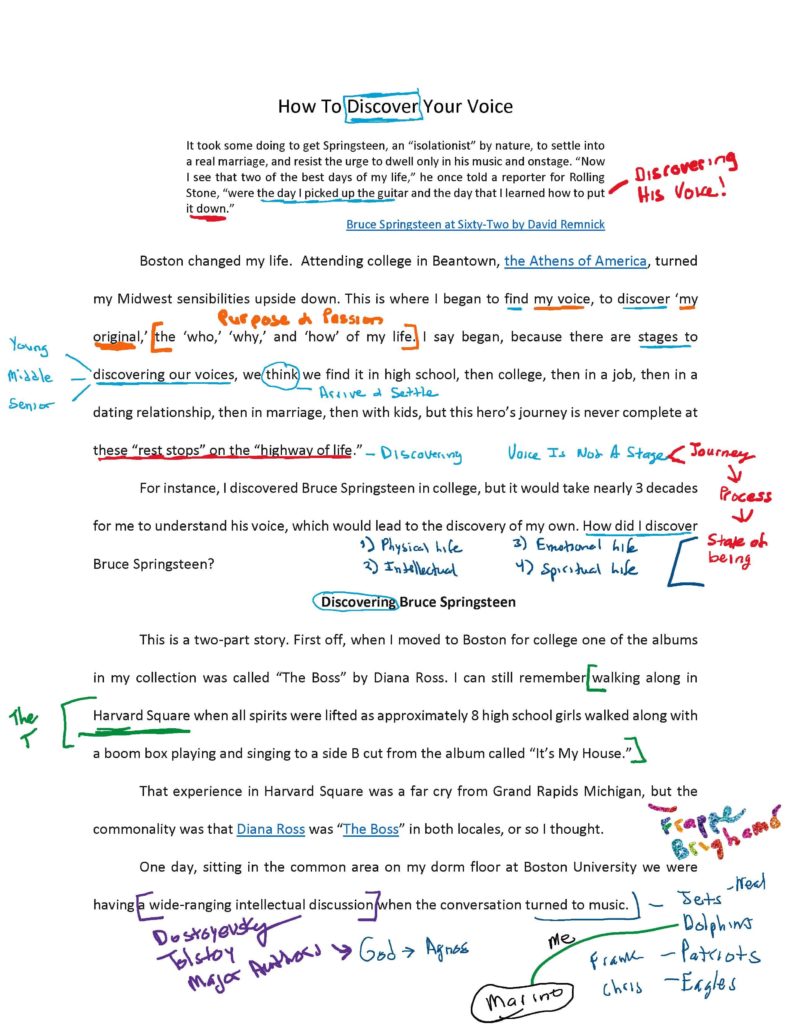

How to Discover Your Voice

October 16, 2020

Russ Ewell

Listen to the podcast series based on this article entitled “Discovering My Voice“

It took some doing to get Springsteen, an “isolationist” by nature, to settle into a real marriage, and resist the urge to dwell only in his music and onstage. “Now I see that two of the best days of my life,” he once told a reporter for Rolling Stone, “were the day I picked up the guitar and the day that I learned how to put it down.”

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Boston changed my life. Attending college in Beantown, the Athens of America, turned my Midwest sensibilities upside down. This is where I began to find my voice, to discover ‘my original’ – the ‘who,’ ‘why,’ and ‘how’ of my life. I say began, because there are stages to discovering our voices, we think we find it in high school, then college, then in a job, then in a dating relationship, then in marriage, then with kids, but this hero’s journey is never complete at these “rest stops” on the “highway of life.”

For instance, I discovered Bruce Springsteen in college, but it would take nearly 3 decades for me to understand his voice, which would lead to the discovery of my own. How did I discover Bruce Springsteen?

Discovering Bruce Springsteen

This is a two-part story. First off, when I moved to Boston for college, one of the albums in my collection was called “The Boss” by Diana Ross. I can still remember walking along in Harvard Square when all spirits were lifted as some girls walked along with a boom box playing and singing to a side B cut from the album called “It’s My House.”

That experience in Harvard Square was a far cry from Grand Rapids Michigan, but the commonality was that Diana Ross was “The Boss” in both locales, or so I thought.

One day, sitting in the common area on my dorm floor at Boston University, we were having a wide-ranging intellectual discussion when the conversation turned to music.

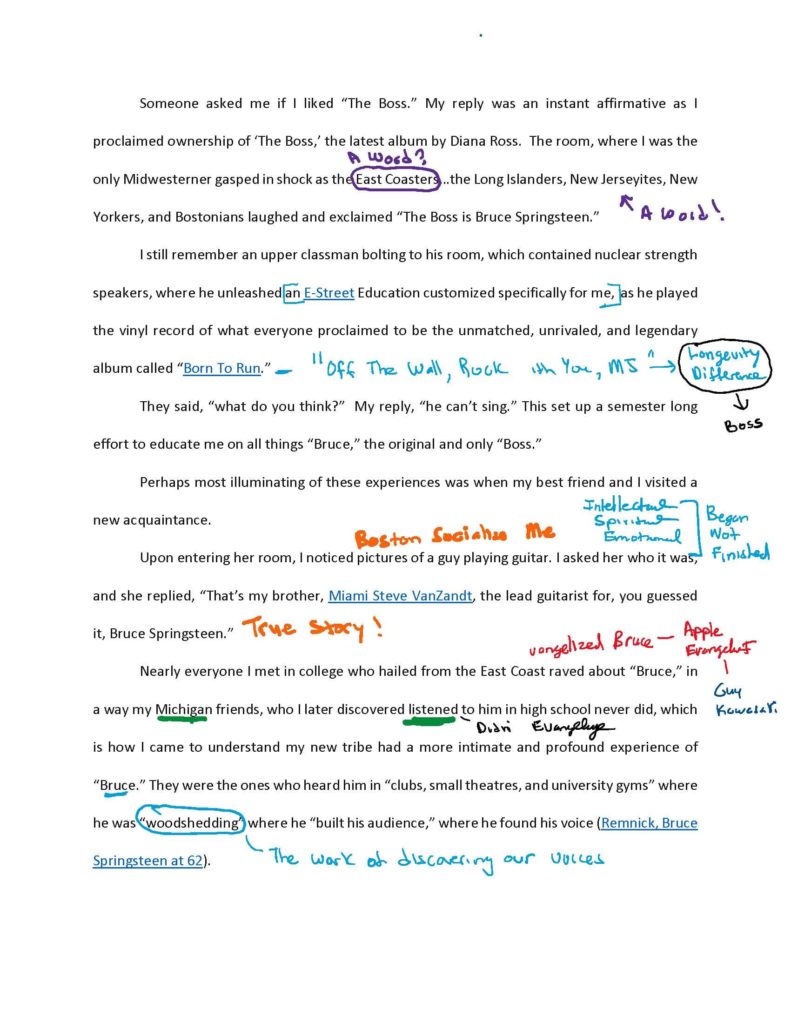

Someone asked me if I liked “The Boss.” My reply was an instant affirmative as I proclaimed ownership of ‘The Boss,’ the latest album by Diana Ross. The room, where I was the only Midwesterner gasped in shock as the East Coasters…the Long Islanders, New Jerseyites, New Yorkers, and Bostonians laughed and exclaimed “The Boss is Bruce Springsteen.”

I still remember an upperclassman bolting to his room, which contained nuclear strength speakers, where he unleashed an E-Street education customized specifically for me, as he played the vinyl record of what everyone proclaimed to be the unmatched, unrivaled, and legendary album called “Born To Run.”

They said, “What do you think?” My reply: “He can’t sing.” This set up a semester-long effort to educate me on all things “Bruce,” the original and only “Boss.”

Perhaps most illuminating of these experiences was when my best friend and I visited a new acquaintance.

Upon entering her room, I noticed pictures of a guy playing guitar. I asked her who it was, and she replied, “That’s my brother, Miami Steve VanZandt,” the lead guitarist for, you guessed it, Bruce Springsteen.

Nearly everyone I met in college who hailed from the East Coast raved about Bruce, in a way my Michigan friends, who I later discovered listened to him in high school never did, which is how I came to understand my new tribe had a more intimate and profound experience of Bruce. They were the ones who heard him in “clubs, small theatres, and university gyms” where he was “woodshedding” where he “built his audience,” where he found his voice (Remnick, Bruce Springsteen at 62).

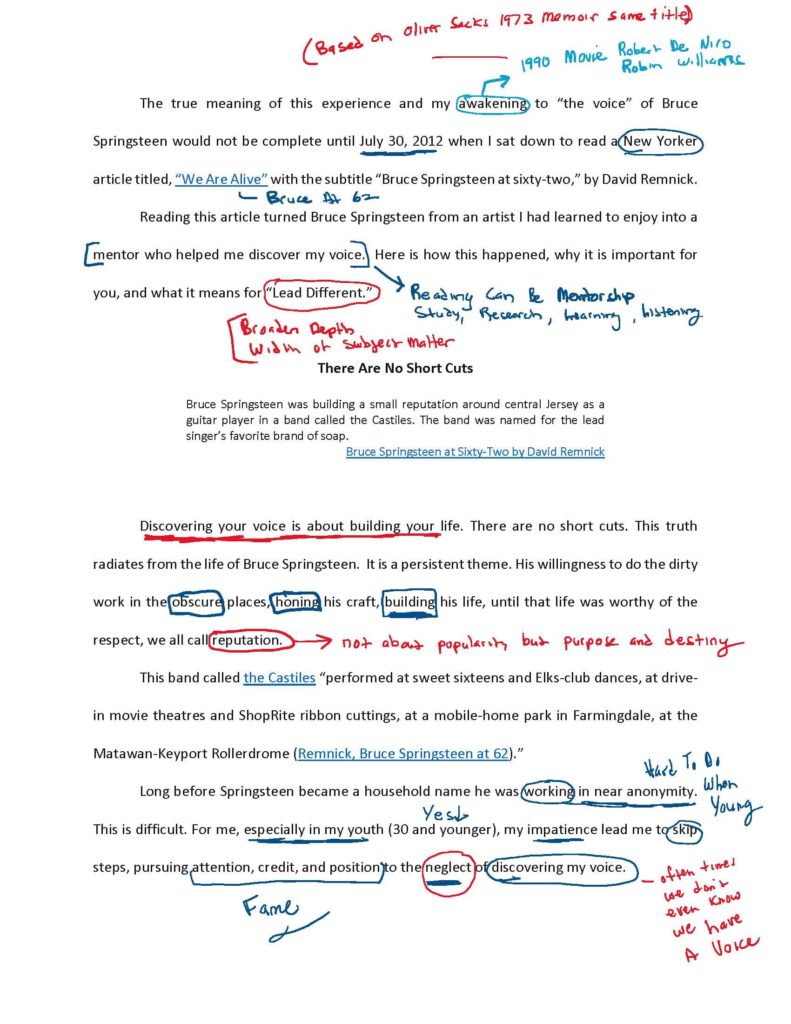

The true meaning of this experience and my awakening to the voice of Bruce Springsteen would not be complete until July 30, 2012 when I sat down to read a New Yorker article titled, “We Are Alive” with the subtitle “Bruce Springsteen at sixty-two,” by David Remnick.

Reading this article turned Bruce Springsteen from an artist I had learned to enjoy into a mentor who helped me discover my voice. Here is how this happened, why it is important for you, and what it means for “Lead Different.”

There Are No Shortcuts

Bruce Springsteen was building a small reputation around central Jersey as a guitar player in a band called the Castiles. The band was named for the lead singer’s favorite brand of soap.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Discovering your voice is about building your life. There are no shortcuts. This truth is a persistent theme throughout the life of Bruce Springsteen: from his willingness to do the dirty work in obscure places, to the way he honed his craft, to how he built his life until that life was worthy of the respect and reputation he now has.

This band called the Castiles “performed at sweet sixteens and Elks-club dances, at drive-in movie theatres and ShopRite ribbon cuttings, at a mobile-home park in Farmingdale, at the Matawan-Keyport Rollerdrome (Remnick, Bruce Springsteen at 62).”

Long before Springsteen became a household name he was working in near anonymity. This is difficult. For me, especially in my youth (30 and younger), my impatience led me to skip steps, pursuing attention, credit, and position.

Unfortunately, each time I skipped steps, I chose superficial advancement over the deep work of discovering my voice. This resulted in the collapse of my life, rather than the building of it. I learned the hard way that there are no shortcuts. Ever.

Talent is Not Enough

In the past several years, Springsteen has been taking requests from the crowd. He has never been stumped. “You can take the band out of the bar, but you can’t take the bar out of the band,” Van Zandt says.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

The mastery of Bruce Springsteen was born out of a bar where he learned to play for countless hours in front of crowds, be they 25, 50, or 100. This is what Miami Steve Van Zandt meant when he said, “You can take the band out of the bar, but you can’t take the bar out of the band.” This is the definition of grit.

Angela Duckworth writes about this quality in her book “Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance,” where she describes the person whose success cannot be explained by talent alone. Afterall, there are many talented people, but few who develop the mastery to make their dreams come true.

In sum, no matter the domain, the highly successful had a kind of ferocious determination that played out in two ways. First, these exemplars were unusually resilient and hardworking. Second, they knew in a very, very deep way what it was they wanted. They not only had determination, they had direction. It was this combination of passion and perseverance that made high achievers special. In a word, they had grit.

Angela Duckworth, Grit: The Power of Passion and Perseverance

We cannot discover our voice unless we combine grit with talent, as the movie the “Natural” tries to point out time and time again, talent is not enough.

Understand the Role of Spirituality

So Jacob was left alone, and a man wrestled with him till daybreak. [25] When the man saw that he could not overpower him, he touched the socket of Jacob’s hip so that his hip was wrenched as he wrestled with the man. [26] Then the man said, “Let me go, for it is daybreak.” But Jacob replied, “I will not let you go unless you bless me.”

Genesis 32:24-26 NIV

Spirituality is the sacred space of our lives where we discover meaning and purpose. Listening to decades of Springsteen music, one can only marvel at his vulnerability: his willingness to not only share his journey, but to help those who listen find their way in the midst of life’s victories and travails.

His music, along with decades of interviews and books reveal a man who has wrestled and wants to teach his audience to wrestle until they experience the blessing. What has surprised me most is his awareness of the importance of the spiritual experience he creates.

Springsteen believed that these worries, and the larger sense of loss and injury, might provide an energy that the tour could draw on. After all these years onstage, he can stand back from his performances with an analytic remove. “You’re the shaman, a little bit, you’re leading the congregation,” he told me.

“But you are the same as everybody else in the sense that your troubles are the same, your problems are the same, you’ve got your blessings, you’ve got your sins, you’ve got the things you can do well, you’ve got the things you f**k up all the time. And so you’re a conduit. There was a series of elements in your life—some that were blessings, and some that were just chaotic curses—that set fire to you in a certain way.”

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Finding our voice must contain a spiritual component, where we learn to overcome.t is in this overcoming that, like Jacob in scripture, we are transformed into the person our inner voice longs for us to be, a longing of the soul that can only be satisfied by this type of growth and change, the type that turns our “unspiritual Jacob” into the “spiritual Israel” (Genesis 32:27-28 NIV)

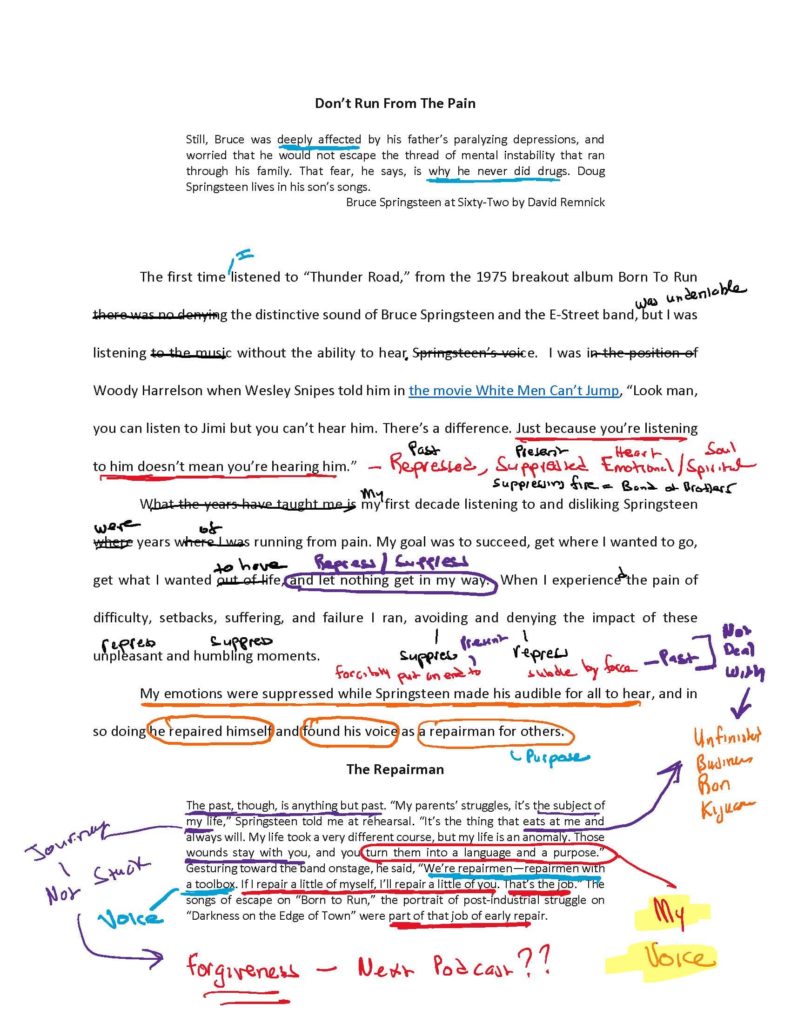

Don’t Run From The Pain

Still, Bruce was deeply affected by his father’s paralyzing depressions, and worried that he would not escape the thread of mental instability that ran through his family. That fear, he says, is why he never did drugs. Doug Springsteen lives in his son’s songs.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

The first time I listened to “Thunder Road,” from the 1975 breakout album Born To Run, the distinctive sound of Bruce Springsteen and the E-Street band was undeniable, but I was listening without the ability to hear. I was Woody Harrelson in the movie White Men Can’t Jump, when Wesley Snipes said to him, “Look man, you can listen to Jimi but you can’t hear him. There’s a difference. Just because you’re listening to him doesn’t mean you’re hearing him.”

My first decade listening to and disliking Springsteen were years spent running from pain. My goal was to succeed, get where I wanted to go, get what I wanted to have, and let nothing get in my way. When I experienced the pain of difficulty, setbacks, suffering, and failure, I ran, avoiding and denying the impact of these unpleasant and humbling moments.

My emotions were suppressed while Springsteen made his audible for all to hear, and in doing so he repaired himself and found his voice as a repairman for others.

The Repairman

The past, though, is anything but past. “My parents’ struggles, it’s the subject of my life,” Springsteen told me at rehearsal. “It’s the thing that eats at me and always will. My life took a very different course, but my life is an anomaly. Those wounds stay with you, and you turn them into a language and a purpose.”

Gesturing toward the band onstage, he said, “We’re repairmen—repairmen with a toolbox. If I repair a little of myself, I’ll repair a little of you. That’s the job.” The songs of escape on “Born to Run,” the portrait of post-industrial struggle on “Darkness on the Edge of Town” were part of that job of early repair.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Life wounds righteously faced lead us on a journey toward our destiny. This is “The Hero’s Journey” about which Joseph Campbell writes, and when this journey is navigated properly like Springsteen we become repairmen and women, people capable of healing ourselves and others, which is the original purpose for which the God of scripture called people into community, that we might heal each other and heal the world.

Finally, beloved friends, be cheerful! Repair whatever is broken among you, as your hearts are being knit together in perfect unity. Live continually in peace, and God, the source of love and peace, will mingle with you.

2 Corinthians 13:11 TPT

This repair mentality is the result of finding your voice. What I have learned is as each year unfolds and my voice gains clarity my life becomes increasingly focused on helping others, rather than merely helping myself.

Be Original

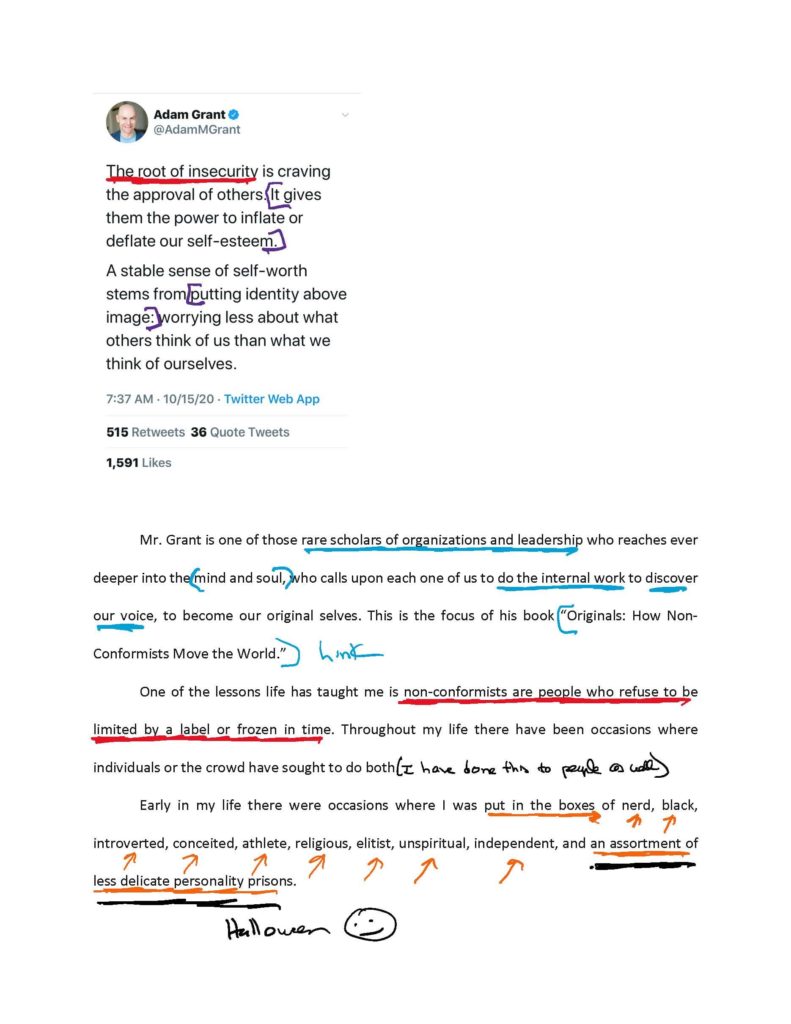

Adam Grant is an organizational psychologist everyone should read or at least follow on Twitter, where he recently wrote:

Mr. Grant is one of those rare scholars of organizations and leadership who reaches ever deeper into the mind and soul, who calls upon each one of us to do the internal work to discover our voice, to become our original selves. This is the focus of his book “Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World.”

One of my lessons learned is non-conformists are people who refuse to be limited by a label or be frozen in time. Throughout my life there have been occasions where individuals or the crowd have sought to both place labels and freeze me in time (I have been guilty of the same).

Early in my life there were occasions where I was put in the boxes of nerd, black, introverted, conceited, athlete, religious, elitist, unspiritual, independent, and an assortment of less delicate personality prisons.

The problem with labels whether they are accurate or inaccurate is over time those who knew us during a specific period of labeling tend to freeze us in time, they refuse to let us grow. On more occasions than I care to remember, people have referred to me with some variation of the aforementioned labels or expected me to live in accordance with their expectations of these labels.

The problem with ‘labels’ and ‘freezing people in time’ is we cannot grow, which prevents us from discovering our voices. For me, this meant breaking free, refusing to allow anyone to keep me as a prisoner to the label they felt most comfortable with or preferred to keep as their definition of me.

Once again Springsteen came to my rescue. Anyone who follows Bruce and his E-Street family will quickly discover “The Boss” is an original.

For Van Zandt, that intensity was a lure. He recognized in Springsteen a drive to create original work. In those days, he said, you were judged by how well you could copy songs off the radio and play them, chord for chord, note for note: “Bruce was never good at it. He had a weird ear. He would hear different chords, but he could never hear the right chords. When you have that ability or inability, you immediately become more original. Well, in the long run, guess what: in the long run, original wins.”

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Time To Woodshed

There is no section of the David Remnick article with more effect on me than when he describes a road trip to see the band Chicago.

In June, 1973, when I was fourteen, I got on a Red & Tan 11-C bus in north Jersey with a couple of friends and went to the city to see a resolutely un-hip and unaccountably popular band called Chicago, at Madison Square Garden. I am not quite sure why I went. We were Dylan fanatics. “Howl,” the Stanley Brothers, Otis Redding, “Naked Lunch,” Hank Williams, Odetta—practically anything I knew or read or heard seemed to come through the auspices of Dylan. Chicago was about as far from the Dylan aesthetic as you could get.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

This was the trip where he caught his first glimpse of “The Boss.”

All the same, I’d paid my four dollars, and I was going to see whatever I could glimpse from our seats. Out trundled the opening act: someone named Bruce Springsteen.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

While reading his account I couldn’t help but remember another college experience. I was invited to join a group who were going to a Bruce Springsteen concert. At that point, Springsteen was the biggest rock star in the world, but I said “no” and have never attended a Springsteen concert in my life. Shame! But back to Remnick’s account.

All the same, I’d paid my four dollars, and I was going to see whatever I could glimpse from our seats. Out trundled the opening act: someone named Bruce Springsteen. The conditions were abysmal, as they often are for opening acts: the houselights were up, the crowd was alternately inattentive and hostile. What I remember was a bandleader as frenetic as Mick Jagger or James Brown, a singer bursting with almost self-destructive urgency, trying to bust through the buzzy indifference of the crowd.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

There it is, the resistance faced by everyone trying to discover their voice: “a singer bursting with almost self-destructive urgency, trying to bust through the buzzy indifference of the crowd.”

Resistance’s goal is not to wound or disable. Resistance aims to kill. Its target is the epicenter of our being: our genius, our soul, the unique and priceless gift we were put on earth to give and that no one else has but us. Resistance means business. When we fight it, we are in a war to the death.

Steven Pressfield, The War of Art

Every now and then I wonder why a particular winner of “The Voice” or “American Idol” fails to become a star. I have wondered why I have not been a star at certain things in my life. I have wondered why incredibly talented people with opportunity have not gone on to do great things in their chosen field of endeavor.

I have learned two things. First, what we start out to do is not necessarily what destiny or God has called us to do. The second, even if we have landed on the right purpose for our lives, there is a resistance we must navigate in order for our voice to rise and be heard to the level of impact for which our souls cry for our lives to have.

At this moment, we get a glimpse of how Bruce Springsteen handles his resistance.

After that show, Springsteen swore to Appel that he would never open or play big venues again. “I couldn’t stand it—everybody was so far away and the band couldn’t hear,” he told Dave Marsh. It was time to woodshed, time to build an audience through constant, intense performance in clubs, small theatres, and university gyms.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Reading “Born To Run” written by Springsteen himself, Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock ‘N” Roll by Marc Dolan, The Promise of Bruce Springsteen by Eric Alterman, or the recent Ghosts, Guitars, and the E Street Shuffle, one thing shines forth about “The Boss,” which is that he didn’t want to be Chicago, the Beatles, or even Bob Dylan. In his heart was a sound, an experience, a voice uniquely his own.

Woodshedding was not about failure, but discovery. It was saying “no” to near certain at the point in his career where he was an opening act for Chicago, and instead choosing to discover his voice.

From that moment on Springsteen lived on food stamps, fired band members, experienced less than favorable reviews, traveled to California from New Jersey only to learn his band was not nearly as good as he thought. At each stage he was paying the price, not so much for success, but to find his voice, confident that when he found his voice, the audience whose hearts were so attuned would find him. This he did, until a critic named Jon Landau, who would eventually become his manager, set the world on fire after seeing Springsteen.

Last Thursday, at the Harvard Square Theatre, I saw my rock ’n’ roll past flash before my eyes. And I saw something else: I saw rock and roll future and its name is Bruce Springsteen. And on a night when I needed to feel young, he made me feel like I was hearing music for the very first time. . . .

He is a rock ’n’ roll punk, a Latin street poet, a ballet dancer, an actor, a joker, bar band leader, hot-shit rhythm guitar player, extraordinary singer, and a truly great rock ’n’ roll composer. He leads a band like he has been doing it forever. . . . He parades in front of his all-star rhythm band like a cross between Chuck Berry, early Bob Dylan, and Marlon Brando.

We Are Alive: Bruce Springsteen at Sixty-Two by David Remnick

Conclusion

“Shapers” are independent thinkers: curious, non-conforming, and rebellious. They practice brutal, nonhierarchical honesty. And they act in the face of risk, because their fear of not succeeding exceeds their fear of failing.

Adam Grant, Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

Springsteen has made me fearless. He has taught me our mission is not to seek popularity, adhere to a label, stay in a box, or be satisfied with the frozen image people of our youth use as their frame for who we are, but we should instead woodshed, do the dirty work behind the scenes and out of the spotlight, until we achieve mastery not only of our craft but of ourselves.

This mastery is not perfection, but the honesty of imperfection seeking to be the architect of perfection through the completion of our own hero’s journey to discover our voice.

When we do this fearlessly, honestly, then it seems to me we are original, we are a “shaper” as described above. Whether we are well known or living quietly in our community, if we have discovered our voice, it is my belief we can all change things, including the world.

The greatest shapers don’t stop at introducing originality into the world. They create cultures that unleash originality in others.

Adam Grant, Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

This journey is not about perfection. Finding our voice, becoming original means navigating internal doubts, personal failure, frustrating rejection, and all the experiences necessary for discovery, because being original is not about appearances on the outside, but settled security on the inside.

Although many originals come across as beacons of conviction and confidence on the outside, their inner experiences are peppered with ambivalence and self-doubt.

Adam Grant, Originals: How Non-Conformists Move the World

What this journey has meant to me, even writing this article, is to set me free to write as I must to fulfill the truth of my journey. I am not one thing -, entrepreneur, writer, pastor, spiritual theologian, inclusion advocate, technologist, applied historian, thought leader -, but I am many things all coming together with the march forward of each year lived in pursuit of discovery, the discovery of my voice.

What about you?